|

|

[Note: this transcription was produced by an automatic OCR engine]

31

Despite this cultural and linguistic homogeneity, there are'variations in some elements

of Western Desert social organisation and kinship. Indeed, although most groups possess

sections, some use six terms Ngaatjatjarra, Ngaanyatjarra or eight subsections Pintupi.

There are also groups not using the section system at all Pitjantjatjara,“‘ Yankunytjatjara.

Another example is the moiety system. While none of the Western Desert groups names matri-

moieties, some have named patri—moieties Mardu and Pintupi. The main social category

classification used by all Western Desert groups is GENERATIONAL moieties cf. White 1981.

Here again, there are some, albeit more limited, variations. A later chapter will discuss these

and illustrate their geographic distribution in the Western Desert.”

Throughout the Western Desert, marriage takes place between cross-cousins and some

persons of identical alternate GENERATIONAL moiety, but difierent generation?’ yet here again

some variations exist. Mandjildjaiaspeaking people, included today with Mardu people,

allow marriage between some people related as actual cross-cousins Tonkinsou 1991:64,

while the Ngaatjatjarra allow marriage only between cross-cousins who are genealogically

and spatially distant at least to the third degree Dousset 1999a.

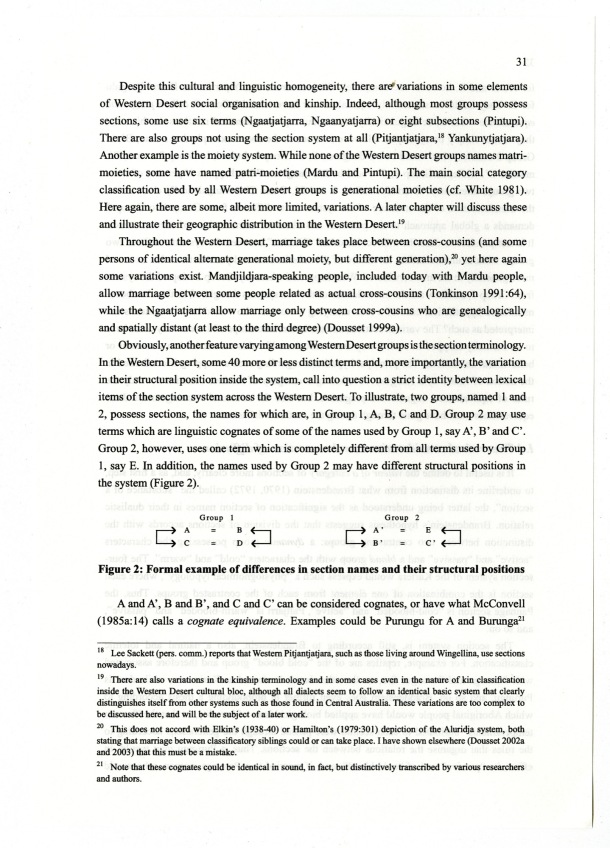

Obviously, another feature varying among Western Desert groups is the section terminology.

In the Western Desert, some 40 more or less distinct terms and, more importantly, the variation

in their structural position inside the system, call into question a strict identity between lexical

items of the section system across the Western Desert. To illustrate, two groups, named 1 and

2, possess sections, the names for which are, in Group 1, A, B, C and D. Group 2 may use

terms which are linguistic cognates of some of the names used by Group 1, say A’, B’ and C’.

Group 2, however, uses one term which is completely different from all terms used by Group

1, say E. In addition, the names used by Group 2 may have different structural positions in

the system Figure 2.

Figure 2: Formal example of differences in section names and their structural positions

A and A’, B and B’, and C and C’ can be considered cognates, or have what McConve]l

1985a:14 calls a cognate equivalence. Examples could he Purlmgu for A and Burunga“

13 Lee Sackett pers. comm. reports that Western Pitjantjarjara, such as those living around Wingellina, use sections

nowadays.

19 There are also variations in the kinship terminology and in some cases even in the nature of kin classification

inside the Western Desert cultural bloc, although all dialects seem to follow an identical basic system that clearly

distinguishes itself from other systems such as those found in Central Australia. These variations are too complex to

be dismissed here, and will be the subject of a later work.

zo This does not accord with Elkin’s 1938-40 or Hamiltmfs l979:30l depiction of the Aluridja system, both

stating that marriage between classificatory siblings could or can take place. I have shown elsewhere Dousset 2002a

and 2003 that this must be a mistake.

2‘ Note out these cognates could be identical in sound, in run, but distinctively transcribed by various researchers

and authors.

|